Self-organizing Wireless Networks, Part 1: An Introduction

Published:

Author: Zhongyuan Zhao

Welcome to the world of wireless networks, where machines talk to each other through the radiowaves. It’s a fascinating domain, but it can also be pretty darn complicated. Now, imagine trying to get all of these devices to work together without a central controller or any set rules. Sounds like a recipe for disaster, right? Well, not necessarily.

In this post, we’ll be exploring how these distributed systems work and how machine learning can help improve their performance. But before we dive into the technical details, let’s take a step back and think about what makes humans such social creatures. How do we manage to navigate crowded spaces, like a busy cafe or a chaotic street, without bumping into each other or getting lost in the crowd? The answer lies in our ability to self-organize. We can form and maintain order in public without an organizer telling us what to do at every moment. And, as it turns out, wireless networks can learn a thing or two from us.

1. What is self-organizing?

Imagine a bustling city, with cars speeding down the streets and people engrossed in their phones while walking. At first glance, it may seem like complete chaos, but upon closer inspection, there’s an unspoken order that everyone follows. In conversation, we take turns speaking, listen attentively, and avoid interrupting. On the road, we stay in our lanes, stop at red lights, and signal before turning. These social norms keep us organized and functioning as a society.

It turns out that the concept of self-organization and following rules also applies to wireless networks. Wireless devices are constantly communicating with each other amid background noise and interference, similar to people talking in a crowded coffee shop (Fig. 1). When organizing a wireless network, there are two options: either we program the devices to follow a central authority, like a cellular base-station directing every move of your phone, or we can design a set of norms that enable wireless devices to self-organize.

But what if the communication infrastructure is destroyed in a natural disaster or you find yourself in a remote area with no signal? In such situations, you can no longer contact your friends with your cell phone. However, with self-organizing wireless networks, communication nodes can quickly form new networks, establish connections, and reroute messages without a centralized controller.

In the upcoming sections, we’ll delve into the world of self-organizing wireless networks and explore their differences from other types of wireless networks.

2. Top-down vs Bottom-up in Networking

Consider the vast difference between top-down engineering systems and bottom-up self-organizing systems. For example, railway and cellular networks are pre-planned networks using dedicated schedulers to guide the physical and data traffics. These networks rely on properly planned infrastructure to function and can be incredibly efficient in resource utilization. Just think about the energy and labor costs of transporting a passenger 1 kilometer by train versus by car.

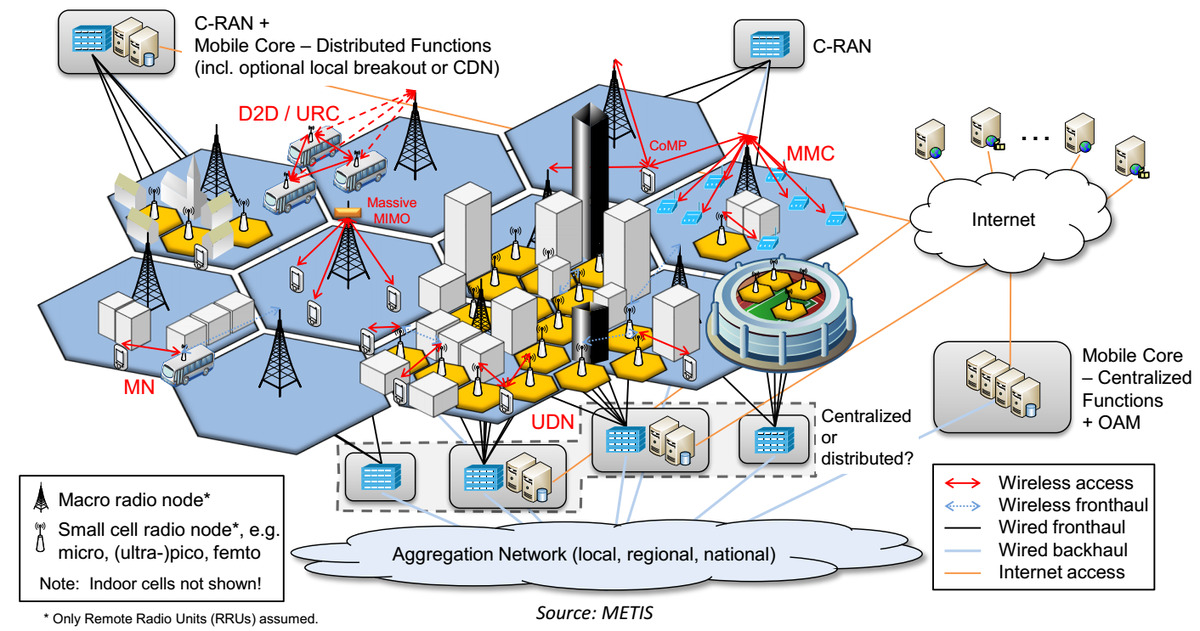

The infrastructure for 5G cellular networks, called cloud radio access network (Cloud-RAN), is a perfect example of top-down design (see Fig. 2). It consists of base-stations that connect to the telecommunication network and the Internet through wired/wireless fronthaul and backhaul networks. These base-stations are carefully planned out according to the population density and terrain, providing network connectivity to mobile devices in a macro or small cell. The cellular base-station manages the transmission of mobile devices attached to it, as well as some of their radio parameters, allowing for efficient resource utilization. These functionalities require descent computing power, dedicated backhaul, and expensive radio transceivers. As a result, running a cellular network requires a significant upfront investment and years of construction, maintenance, and upgrades.

In contrast, Wi-Fi networks are organized bottom-up, with anyone able to install a Wi-Fi router (access point) at home. The medium access control (MAC) of Wi-Fi is self-organized, which means that the access point does not schedule transmissions or manage the parameters of devices attached to it. Instead, when a Wi-Fi device has data packets to transmit, it first listens to the medium for a brief time, and if there is no activity, it begins transmission. This self-organizing feature makes Wi-Fi access points 1000 times cheaper than cellular base-stations, and explains why Wi-Fi is so successful. In fact, as of 2022, 51% of internet traffic goes through Wi-Fi, while only 19.6% of that goes through cellular networks [Cisco VNI report, 2017-2022, Fig. 22].

However, the listen-before-talk approach used in Wi-Fi MAC only works for small networks. When there are many Wi-Fi devices in a hotspot, there may be too many collisions, causing congestion even if the total demand for bandwidth is not exceeding the capacity of the Wi-Fi access point. You may have experienced such congestions in a café, hotel, or library. In other words, the Wi-Fi protocal cannot always allocate resource efficiently when the network is crowded.

3. Why self-organizing wireless networks?

Let’s take a closer look at why self-organizing wireless networks are so important.

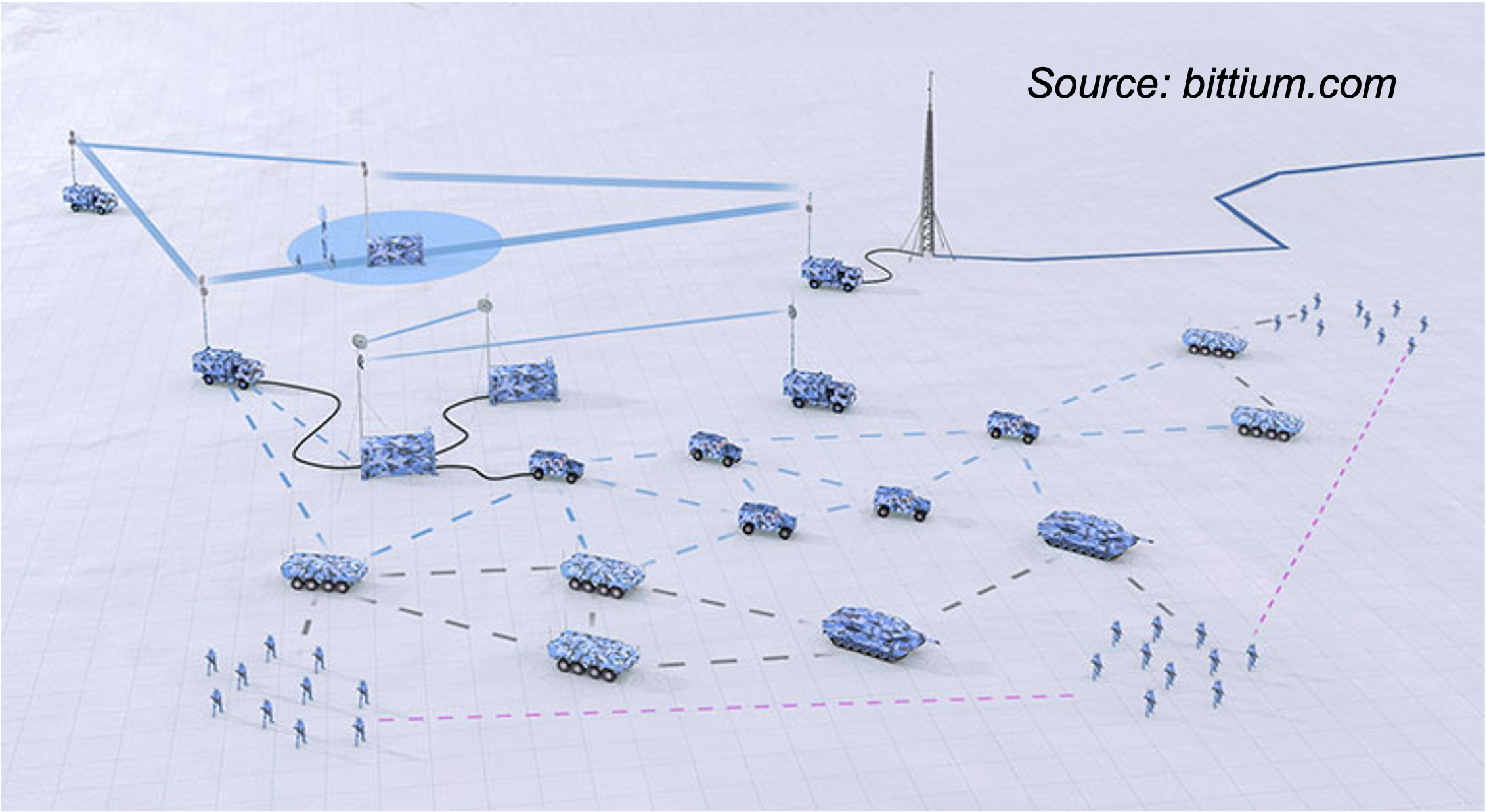

Despite their high efficiency, infrastructure-based networks can be inflexible. The availability of cellular and Wi-Fi network services is limited to areas where cables, fibers, base-stations, and access points have already been installed. Self-organizing networks, on the other hand, are much more adaptable, making them an attractive option for applications where flexibility is key. Take wireless ad-hoc and sensor networks for example. They are often used in harsh or hostile environments, such as disaster areas, remote locations, and even battlefields (see Fig. 3), where traditional infrastructure is impractical. In these cases, self-organizing wireless networks provide critical communication capabilities, enabling users and sensors to establish connections quickly and efficiently without relying on an existing infrastructure.

The self-organizing nature of wireless ad-hoc networks gives them a unique topology compared to cellular and Wi-Fi networks, which rely on direct links between user devices and nearby base-stations or access points. In contrast, wireless ad-hoc networks allow data packets to travel over multiple hops through intermediate user devices to reach their destination, as depicted in Figure 3. This makes them part of a broader class of networks called wireless multihop networks, where each user device not only sends and receives its own data packets, but also helps relay traffic for other devices.

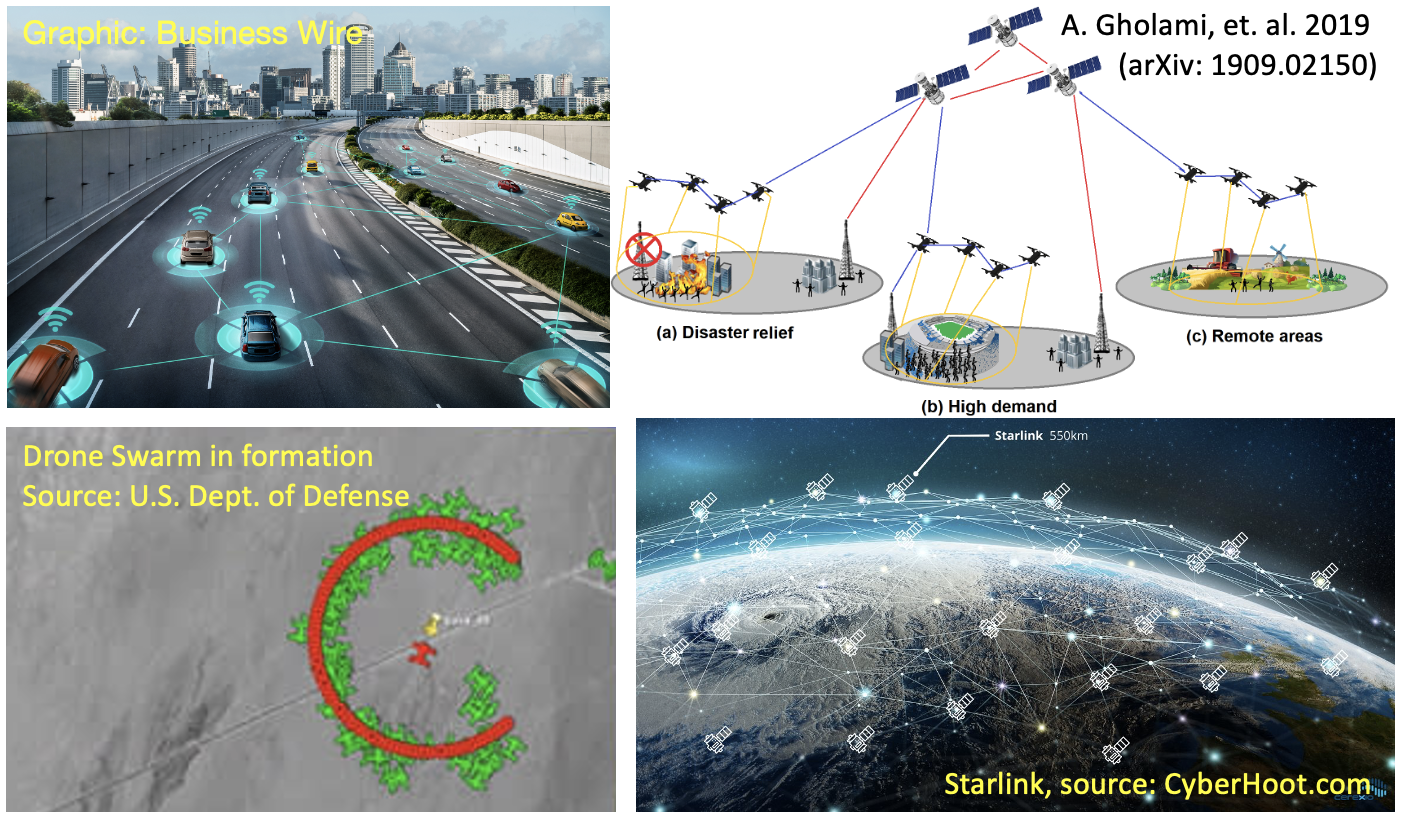

Wireless multihop networks are playing an increasingly important role in many emerging civilian applications, such as smart vehicles, drone fleets, the Internet of Things (IoT), and 5G and beyond (wireless backhaul networks that links base-stations in small cells, drones, and CubeSats [Akyildiz 2022]). As illustrated in Fig. 4 (left), the exchange of safety-critical information (or control messages) among traveling vehicles (drones), for example, requires ultra-low latency and seamless network coverage. To meet such requirements, it is better to establish a direct connection between neighboring vehicles (drones) rather than placing a base-station in the middle.

In 5G and beyond, wireless multihop networks can also serve as wireless backhaul networks that connect base-stations in small cells or those carried by drones and CubeSats to the Internet (Fig. 4 right). Small cells are for highly populated hotspots, such as central business districts, schools, and residential areas (see Fig. 2), whereas drone and CubeSat-assisted wireless networks are for temporary hotspots and non-terrestrial communications, such as oceans, airplanes, mountains, and deserts. For small cells, wireless backhaul can avoid the high cost and inconvenience of installing wired backhaul, while for drone and CubeSat-assisted networks, wireless backhaul is the only option [Akyildiz 2022].

Wireless multihop networks might also help address the challenge of massive access in the Internet of Things (IoT) [Chen 2021]. The popularity of IoT devices could lead to very high connectivity density, with projections of up to 10 million wireless connections per $km^2$ by 2030 [Chen 2021]. Although the real bandwidth required by their payloads is not high, the overheads of handshaking and authorization generated by these IoT devices under existing cellular architecture could consume all the bandwidth, jamming the entire network. If these IoT devices can form self-organizing networks, the situation could be significantly improved.

4. Synchronization

Another dimension of the organization of wireless networks is synchronization. Synchronization is essential in wireless communication to ensure that the transmitter and receiver have a common frame of reference for timing and frequency. This is due to the fact that each wireless device has its own independent clock source, typically a crystal oscillator, which can cause timing drift and frequency offset between devices. If left unsynchronized, this can result in data transmission errors, collisions, and other performance issues.

Like infrastructure, synchronization can improve the resource efficiency and performance, at the cost of reduced flexibility. Based on infrastructure and synchronization, wireless networks can be categorized as follows:

| synchronized | random access | |

|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure | Cellular, 5G networks | Wi-Fi |

| Ad hoc | Vehicular/Flying/Tactical Ad-hoc Networks | Wireless Ad hoc / Sensor Networks |

In synchronized networks, wireless devices are synchronized to the same clock, usually by GPS signal, enabling them to communicate on accurately defined time slots without collisions. Synchronized networks offer improved performance in throughput, mobility, and resource efficiency.

In random access networks, devices are not synchronized, which leads to overhead in establishing a link between devices. This limits the performance and resource efficiency of random access networks. However, the lack of synchronization makes it easier for devices to self-organize, resulting in greater flexibility, lower energy consumption, and lower cost of devices.

It is important to note that both random access and synchronization are necessary for wireless communication. Cellular protocols, for example, have a dedicated random access channel for new devices to join the network. In Wi-Fi and other random access networks, the receiver needs to synchronize itself to the transmitter to decode the data. The degree of synchronization and random access required in a network depends on the specific application and the trade-offs between performance, resource efficiency, and flexibility.

5. Summary

So far, we’ve discussed three key aspects of wireless network organization: scheduling, topology, and synchronization. We’ve learned that self-organizing wireless networks prioritize flexibility and reliability over performance and resource efficiency, and are designed to function without the help of infrastructure. Using principles such as listen-before-talk, multihop topology, and random access, these networks can operate even in situations where traditional network infrastructure is not feasible or able to meet the requirements.

In part 2 of this blog post, we’ll delve into link scheduling, a key component in organizing wireless multihop networks. We’ll explore how distributed link scheduling can be formulated and solved, and show how it can be improved through the use of machine learning and graph neural networks to achieve maximum efficiency. We’ll also discuss the broad implications of this new approach for the future of networking. So, stay tuned for a more in-depth look at self-organizing wireless networks!

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the valuable assistance of ChatGPT in refining and improving the presentation of this article (see earlier version). The author would also like to express special gratitude to Derek Muller, popularly known as Veritasium, whose unique linguistic style was incorporated into this post. Derek Muller’s engaging and accessible presentation of complex scientific concepts has inspired the author’s writing and helped make this article more engaging and accessible to a wider audience.

References

- [Chen 2021] X. Chen, D. W. K. Ng, W. Yu, E. G. Larsson, N. Al-Dhahir,and R. Schober, “Massive access for 5g and beyond,”IEEE Journal of Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 615–637, 2021.

- [Akyildiz 2022] I. F. Akyildiz, A. Kak, and S. Nie, “6G and beyond: The future of wireless communications systems,” IEEE Access, vol. 8,pp. 133995–134030, 2020.