Self-organizing Wireless Networks, Part 2: Distributed Link Scheduling

Published:

Author: Zhongyuan Zhao

Welcome back to our series on self-organizing wireless networks! In part 1 of this series, we introduced the concept and concerns of wireless networks, and discussed the importance of distributed solutions. In this post, we’ll be delving into the topic of distributed link scheduling, a key component in the organization of wireless multihop networks. We’ll first explore how classic distributed schedulers work, and then how they can be enhanced with machine learning and graph neural networks. Plus, we’ll discuss the implications of this approach for the future of wireless networking and distributed systems. So sit back, relax, and get ready to dive into the world of distributed link scheduling in wireless networks!

1. Routing and scheduling

In wireless multihop networks, the responsibility of networking falls on user devices themselves. They not only transmit and receive their own data packets, but also help relay traffic for other devices. This self-organizing capability is achieved through two core functionalities: distributed routing and distributed scheduling.

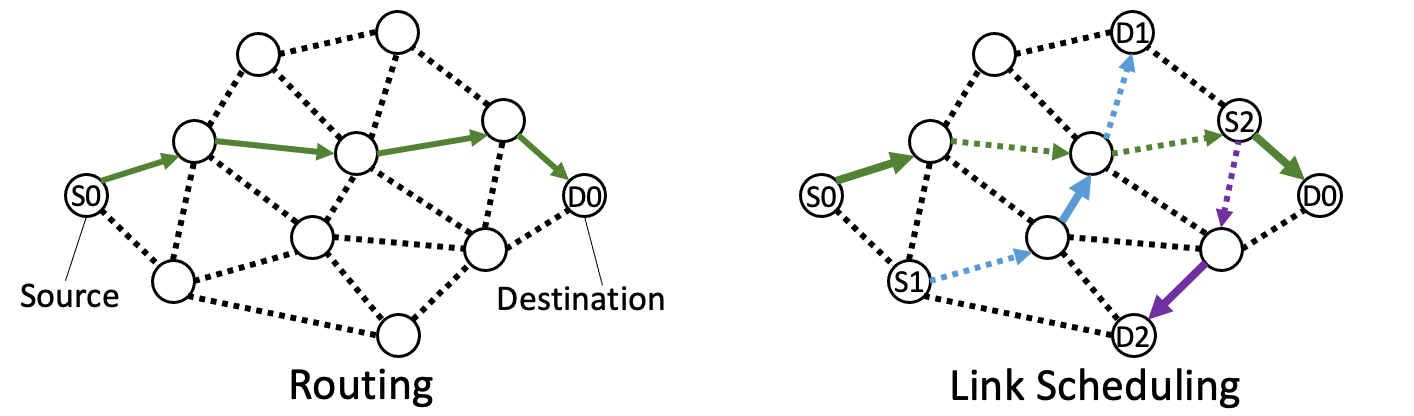

Routing involves finding the optimal path for packets to travel from their source to destination, such as the solid green path in Fig.5 (left), while link scheduling determines which links should be activated in each time slot, as illustrated by the solid edges in Fig.5 (right).

However, the unpredictable and dynamic nature of wireless networks makes routing and scheduling more challenging than in wired networks. Link scheduling, in particular, is limited by the fact that a node with a single radio transceiver can only communicate with one of its neighbors in a given time slot.

In the following section, we will discuss a simple form of distributed link scheduling.

2. Distributed Link Scheduling

In wireless multihop networks, links share the same wireless medium, which means that if two nearby links transmit simultaneously, they will interfere with each other and fail to communicate successfully. Therefore, it is crucial to avoid scheduling conflicting links to transmit at the same time.

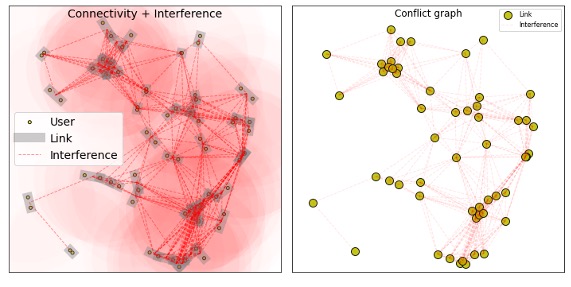

2.1 Conflict graph

To represent these interference relationships between links in the network, we use a conflict graph. The conflict graph is a graph where each vertex represents a link in the network, and an edge exists between two vertices if the corresponding links conflict with each other. The edge can represent either physical or logical interference. Figure 6 shows an example of mapping a wireless multihop network to its conflict graph.

2.2 Maximum weighted independent set problem

Using a conflict graph allows us to formulate the link scheduling problem as an optimization problem on the graph, where we aim to find the maximum-weight independent set. An independent set is a set of vertices where no two vertices are adjacent (i.e., no two links conflict with each other), and the maximum-weight independent set is the independent set with the highest sum of vertex weights.

The vertex weight, which is defined as the utility of scheduling that link, represents the importance of that link in the network. By solving the MWIS problem, a valid schedule can be found that not only avoids conflicting links but also maximizes the total utility.

We can formally define the distributed link scheduling as follows: given a conflict graph $\mathcal{G}(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{E}, \mathbb{u})$, an optimal schedule $\boldsymbol{v}^*$ is found by solving the following MWIS problem:

\begin{align} & \boldsymbol{v}^* = \mathop{\operatorname{arg\,max}}\limits_{\boldsymbol{v}\subseteq \mathcal{V}} \,\, \sum_{v\in\boldsymbol{v}} u(v) \label{eq:mwis} \\ \text{s.t. } & (v_i, v_j)\notin \mathcal{E}\;, \forall \, v_i, v_j \in \boldsymbol{v}. \label{eq:mwis:constraint} \end{align}

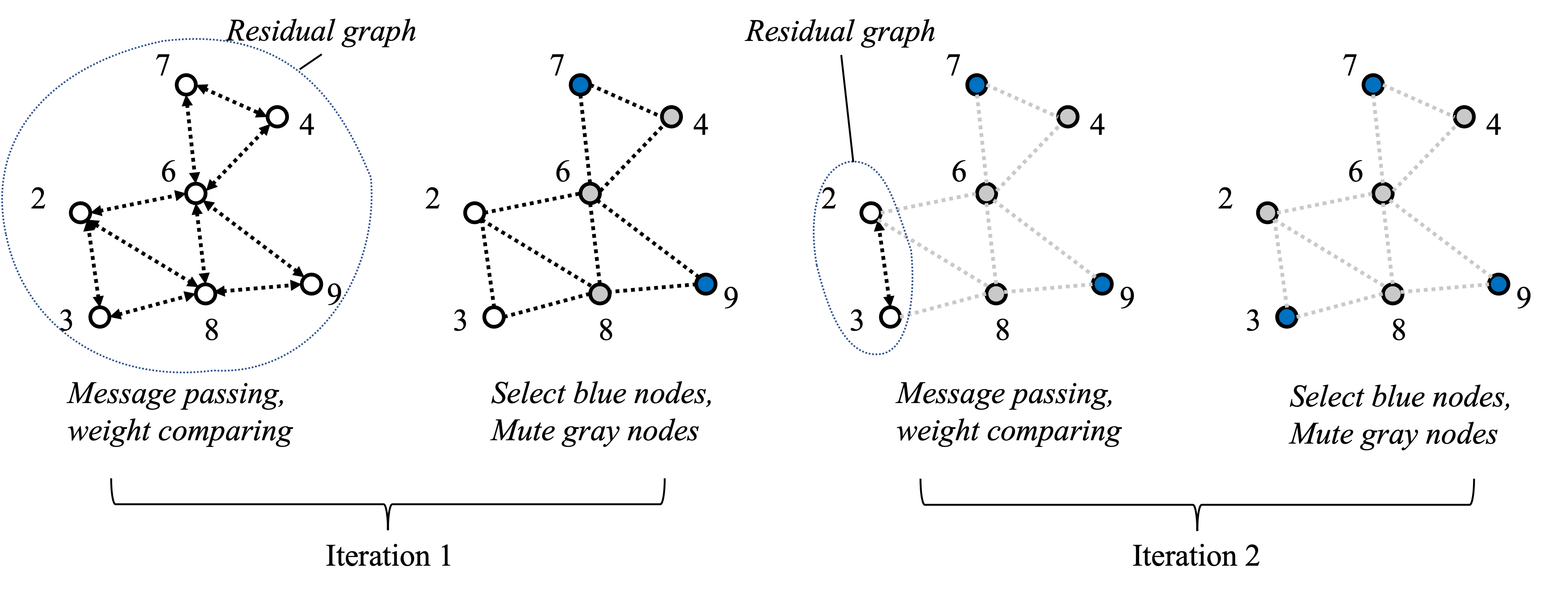

2.3 Distributed Local Greedy Solver

However, finding the optimal solution to the MWIS problem is known to be NP-hard, which makes it computationally infeasible for large-scale networks. To address this challenge, researchers have proposed various heuristics to quickly find an independent set that has a total weight close to the maximum value. One promising approach is the Local Greedy Solver/Scheduler (LGS) (Joo 2012 TMC), a distributed method that iteratively selects vertices with the largest weight in their local neighborhood and then remove the selected ones and their interfering neighbors, until no vertices are left.

The LGS is particularly promising as it has been shown to achieve about $86\%-90\%$ of the optimal performance on some random graphs (Zhao 2022 TWC) while only requiring local information exchange among neighboring nodes. Figure 7 illustrates how LGS solve a MWIS problem step-by-step in a distributed manner. For a more in-depth understanding of this algorithm, readers may refer to the study by the original paper (Joo 2012 TMC).

Next, let’s find out how to use machine learning and graph neural networks to enhance LGS to produce even closer approximations to the optimal solution.

3. Distributed Scheduling with Graph Neural Networks

3.1 What are Graph Neural Networks?

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are a powerful class of machine learning models specifically designed to operate on graph-structured data, such as social networks, transportation networks, and, most importantly, wireless networks. GNNs utilize the network structure to learn features of nodes and edges, as well as the global structure of the entire graph, making them a powerful tool for modeling complex networks.

At the heart of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) is an iterative process of aggregating and updating the features of nodes and their neighbors. This process uses a set of learnable parameters shared across all nodes in the network, allowing for efficient and scalable learning. One of the key advantages of GNNs is that they can be executed in a distributed manner, where each node performs lightweight local computations based on its own information and that of its neighbors. This distributed execution is particularly important in wireless networks, where individual nodes often have limited computing resources and memory. Despite these limitations, the network as a whole can still perform powerful tasks, making GNNs an ideal solution for large-scale wireless networks.

In our approach, we utilize a single layer graph convolutional neural network (GCN) to perform the link scheduling task. The local computation at a vertex (link) $v\in\mathcal{V}$ is shown in (3), where $u(v)$ is the utility of link $v$, $d(v)$ is the node degree of $v$, $\mathcal{N}(v)$ represents the set of neighbors of $v$ on the conflict graph, and $\sigma(\cdot)$ is an element-wise activation function.

\begin{equation} z(v) = \sigma\Bigg( u(v) \, \theta_{0} + \Bigg[ u(v) - \sum_{v_i \in \mathcal{N}(v)}\frac{u(v_i)}{\sqrt{d({v})d({v_i})}} \Bigg]\theta_{1} \Bigg), \end{equation}

Notably, the GCN model only contains two learnable parameters $\theta_{0}$, $\theta_{1}$, allowing it to be executed on resource-constrained wireless devices.

3.2 Option 1: Scheduling as binary classification

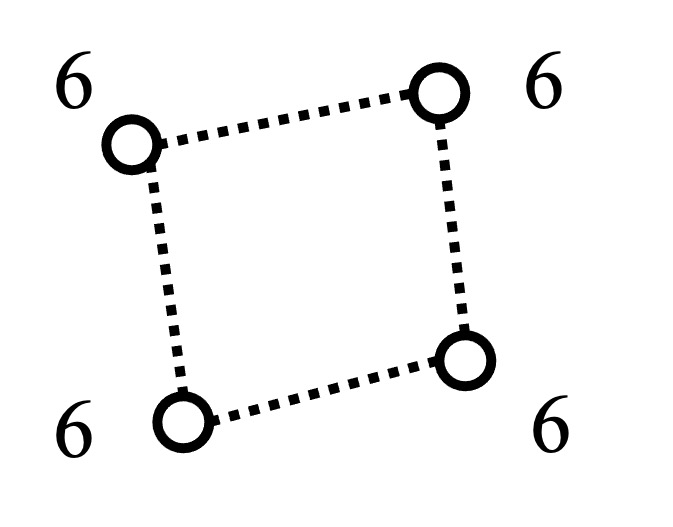

In the context of distributed link scheduling, one straightforward approach is to formulate the problem as a binary classification task, where a link is classified as either transmitting or remaining silent. However, this approach often performs poorly, as it fails to consider the potential conflict between neighboring links.

For example, in the conflict graph in Figure 8, each vertex (link) has the same utility and neighborhood topology. The GNN would predict similar probabilities for all four links. If the predicted probabilities exceed 0.5, the scheduler would schedule all links to transmit, leading to collision and communication failure.

To further elaborate on the challenges of formulating link scheduling as a binary classification problem, it’s worth noting that in addition to poor performance, such an approach requires a labeled training dataset, which is difficult to obtain due to the computational complexity of finding the optimal label of NP-hard MWIS problems.

3.3 Option 2: GCN-LGS

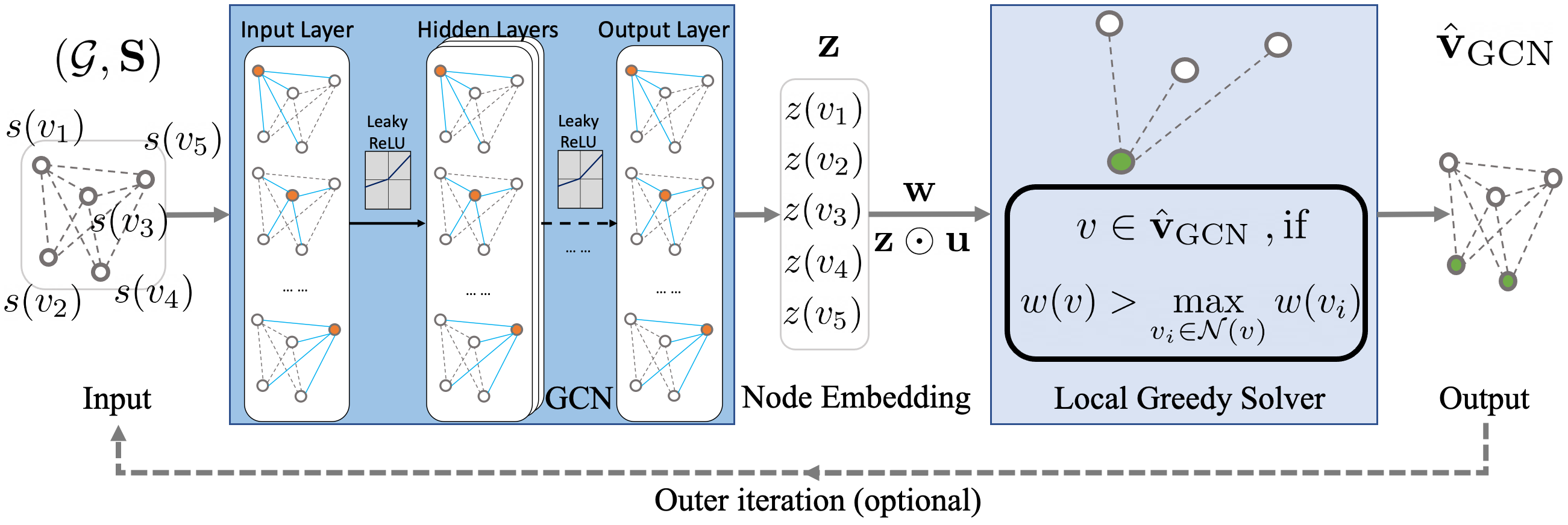

To avoid the pitfalls of a binary classifier, we took a different approach and proposed an innovative method called GCN-LGS. This technique incorporates Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) into the algorithmic framework of the distributed greedy scheduler LGS, as shown in Figure 9.

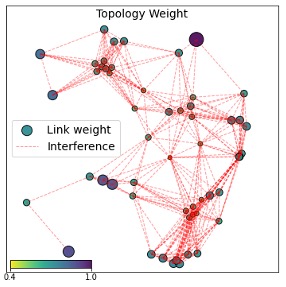

The GCN generates node embeddings, denoted as $\mathbb{z}$, which includes $z(v)$ for all $v\in\mathcal{V}$. These embeddings are used as topological multipliers for the utility $\mathbb{u}$, resulting in a topology-aware utility of $w(v) = z(v)u(v)$. The cool thing about this topological multiplier $z(v)$ is that it can be re-used for multiple time slots until the topology changes. In this case, $z(v)$ can be viewed as the predicted probability of link $v$ being scheduled for the whole sampling space of its link utility $u(v)$. In Figure 10, we visualize the topological multipliers of the conflict graph in Figure 6.

By running LGS based on this topology-aware utility, we are able to leverage the topological importance of a vertex to improve the approximation ratio of the scheduler. For example, if a vertex is peripheral, we increase its original utility $u(v)$, whereas if it has many conflicting neighbors, we discourage it from being scheduled. Overall, this approach allows us to take into account the topology of the conflict graph to improve the performance of the LGS.

Training GCN-LGS is a challenging task that requires the development of effective reinforcement learning schemes. Several approaches have been proposed to address this challenge, ranging from ad-hoc reinforcement learning (Zhao 2021 ICASSP) to a dedicated deterministic policy gradient (Zhao 2022 TWC). Our recent ICLR paper (Zhao 2023 ICLR) presents a more general framework that offers a promising direction for future research. Interested readers can refer to our publications for more detailed information on these approaches.

4 Demonstration

In this demonstration, we compare the performance of two different distributed link schedulers in simulated wireless multihop networks: the Local Greedy Solver/Scheduler (LGS) and the GCN-enhanced LGS. The two simulations, shown side by side in Figure 11, are the same in every aspect except using different scheduling algorithms. The pink circle around each user device represents its interference zone, a thick gray line represents a potential link between two user devices, and a green line represents an activated/scheduled link.

The curves in the right window of Figure 11 are the throughputs achieved by these two schedulers across time. It is evident that the GCN-enhanced LGS consistently outperforms the LGS in terms of total throughput, even in the face of changing network topologies due to the random walks of individual nodes. It is worth noting that the GCN does not need to be retrained for each new topology, as it can automatically generalize to different topologies.

For a more comprehensive comparison of these distributed schedulers, we invite readers to explore our paper (Zhao 2022 TWC).

5 Summary

Let’s take a moment to recap what we’ve covered so far. We began by introducing routing and scheduling and then explored how to formulate the problem of link scheduling in wireless multihop networks as a maximum weighted independent set problem. We then introduced the Local Greedy Solver/Scheduler (LGS), a distributed heuristic that is simple and easy to implement.

Next, we delved into how to use Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to enhance LGS, leveraging the advantages of GNNs in learning graph structure and distributed execution. We also discussed the drawbacks of using GCNs as a binary classifier in solving MWIS and how that led us to propose the GCN-LGS approach.

Our simulations revealed that GCN-enhanced LGS consistently outperforms LGS in terms of total throughput, even as the network topology changes. It’s worth noting that our GCN model is tiny, with only two learnable parameters, making it well-suited for low-end wireless devices like sensors and IoT devices. Yet, when incorporated into our GCN-LGS framework, it closes the optimality gap of LGS by a third to a half (see Zhao 2022 TWC).

Overall, we have demonstrated that GCN-LGS is a promising approach for solving the distributed link scheduling problem in wireless multihop networks. By combining the power of graph neural networks and distributed heuristics, we can achieve improved performance and more efficient use of network resources.

6. Implications for Future Networked Systems

The GCN-LGS approach we introduced in this post has far-reaching implications for the design and optimization of self-organizing wireless networks and other distributed systems.

Essentially, we train an $L$-layer Graph Neural Network to adjust the importance of each wireless link according to the topology of its $L$-hop interfering neighborhood. By doing so, our prescribed scheduler (LGS) can make better decisions and increase the overall throughput of the wireless network. It’s like individually adjusting the cycling period of each traffic light in a city based on its nearby road network to improve the overall traffic flow.

By leveraging the power of Graph Neural Networks to learn the structure of the network, we are able to enhance traditional distributed algorithms and bring intelligence to the network edge. This opens up a range of possibilities for improving other tasks in self-organizing wireless networks, such as routing, resource allocation, and energy management. For example, we have shown its applications in improving the latency and overhead of scheduling and routing in a series of papers (Zhao 2021 ICASSP, Zhao 2022a ICASSP, Zhao 2022b ICASSP, Zhao 2023 ICASSP).

Moreover, this approach can be extended to other distributed systems, including robot swarms, vehicle/drone fleets, edge computing, and the internet of things, where each node has limited computing resources and the network topology can be dynamic. By reducing the dependence on centralized coordination and control, our learnable distributed algorithms can improve the efficiency, scalability, and robustness of large-scale networked systems.

In our recent ICLR paper (Zhao 2023 ICLR), we took the GCN-LGS approach to the next level with our new GDPG-Twin framework. This generalization of the GCN-LGS approach allows us to tackle an even wider range of problems in routing and scheduling, as well as other network-related tasks. With the GDPG-Twin, we have opened up exciting new opportunities to learn and achieve long-term strategic goals through distributed and parallel decisions, leading to potentially intelligent swarms and networks.

In summary, the GCN-LGS approach represents a promising direction for the development of intelligent and self-organizing distributed systems, with potential applications in a wide range of domains, from wireless networks to edge computing and beyond. We invite researchers and practitioners to explore the potential of this approach and join us in shaping the future of distributed intelligence.

Acknowledgements

The content of this article is created based on published research sponsored by the Army Research Office under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-19-2-0269. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

The presentation of this article is refined and improved with the help of ChatGPT.

References

- (Joo 2012 TMC): Changhee Joo and Ness B. Shroff, " Local Greedy Approximation for Scheduling in Multihop Wireless Networks," in IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 414-426, March 2012, doi: 10.1109/TMC.2011.33. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMC.2011.33

- (Zhao 2021 ICASSP): Zhongyuan Zhao, Gunjan Verma, Chirag Rao, Ananthram Swami, Santiago Segarra, " Distributed Scheduling Using Graph Neural Networks," IEEE ICASSP 2021, pp. 4720-4724, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9414098

- (Zhao 2022a ICASSP): Zhongyuan Zhao, Gunjan Verma, Ananthram Swami, Santiago Segarra, " Delay-Oriented Distributed Scheduling Using Graph Neural Networks," IEEE ICASSP 2022, pp. 8902-8906, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9746926

- (Zhao 2022b ICASSP): Zhongyuan Zhao, Ananthram Swami, Santiago Segarra, " Distributed Link Sparsification for Scalable Scheduling using Graph Neural Networks," IEEE ICASSP 2022, pp. 5308-5312, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9747437

- (Zhao 2022 TWC): Zhongyuan Zhao, Gunjan Verma, Chirag Rao, Ananthram Swami, Santiago Segarra, " Link Scheduling Using Graph Neural Networks," accepted to IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2022.3222781

- (Zhao 2023 ICLR): Zhongyuan Zhao, Ananthram Swami, Santiago Segarra, " Graph-based Deterministic Policy Gradient for Repetitive Combinatorial Optimization Problems," The 11th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2023, pp. 1-21, https://openreview.net/forum?id=yHIIM9BgOo

- (Zhao 2023 ICASSP): Zhongyuan Zhao, Bojan Radojičić, Gunjan Verma, Ananthram Swami, Santiago Segarra, " Delay-aware Backpressure Routing Using Graph Neural Networks," accepted to IEEE ICASSP 2023, arXiv 2211.10748 . https://arxiv.org/pdf/2211.10748.pdf